Everybody loves photo(video) booths

Create a (branded) experience, record a video automatically and send it to the user - how hard can it be? Turns out, it gets complicated pretty quickly!

I have done quite a few custom photo-booth projects (usually incorporating video rather than still images) over the years, and while I can't say I always understood the appeal from an "experience design" point of view, I certainly learned a lot. The basics are simple enough (after all, photo-booths have existed for decades) but the addition of video recording and the need to produce shareable "digital takeaways" certainly takes it to another level, technically.

Design / Interface Challenges

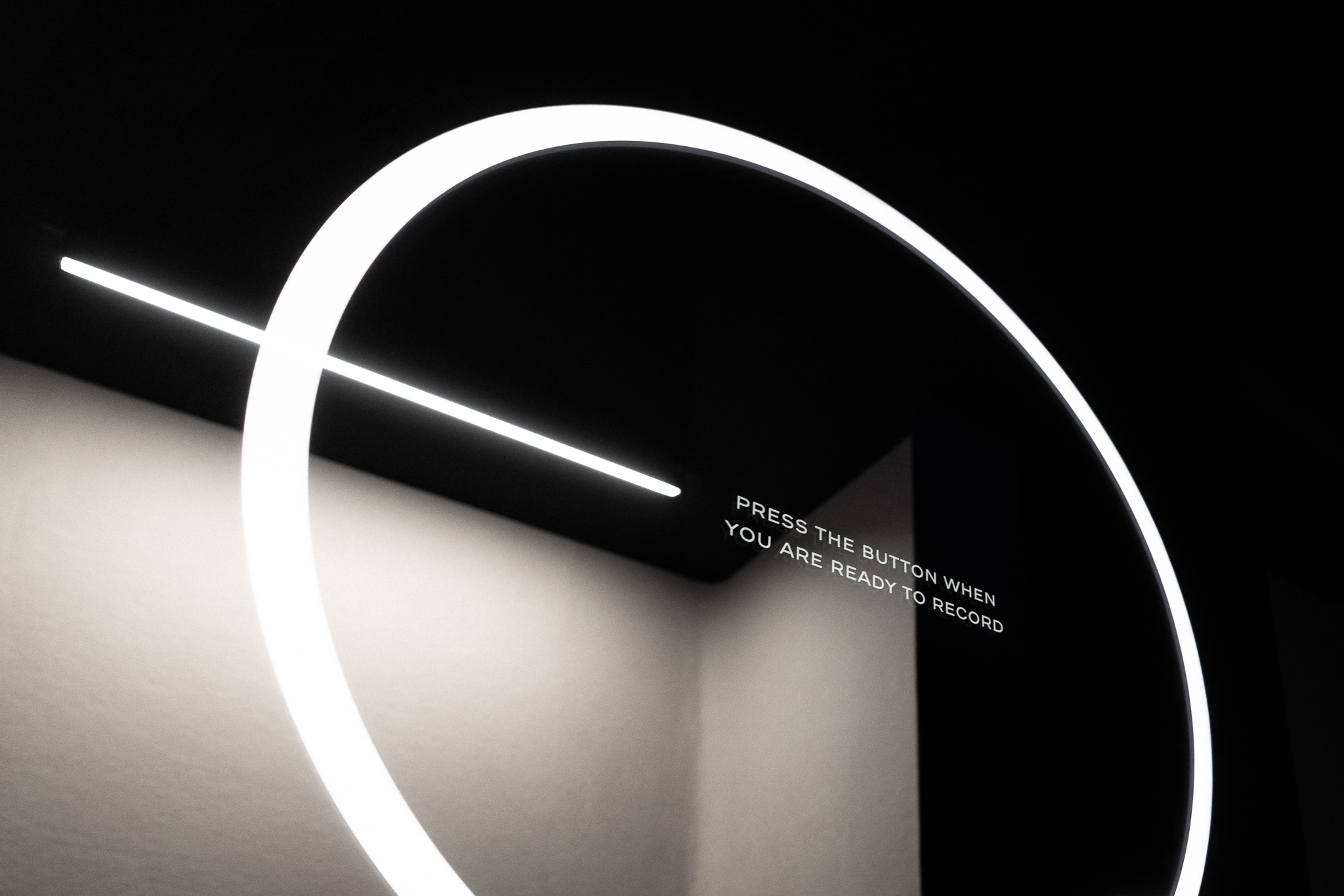

The first challenge is giving the visitor something to do that makes it seem worth recording. Some examples: infinity mirrors, projecting graphics onto people's faces, playing with dynamic lighting, turning their body movements into generative graphics (e.g. with a Microsoft Kinect controller) or applying wild filters onto the video feed.

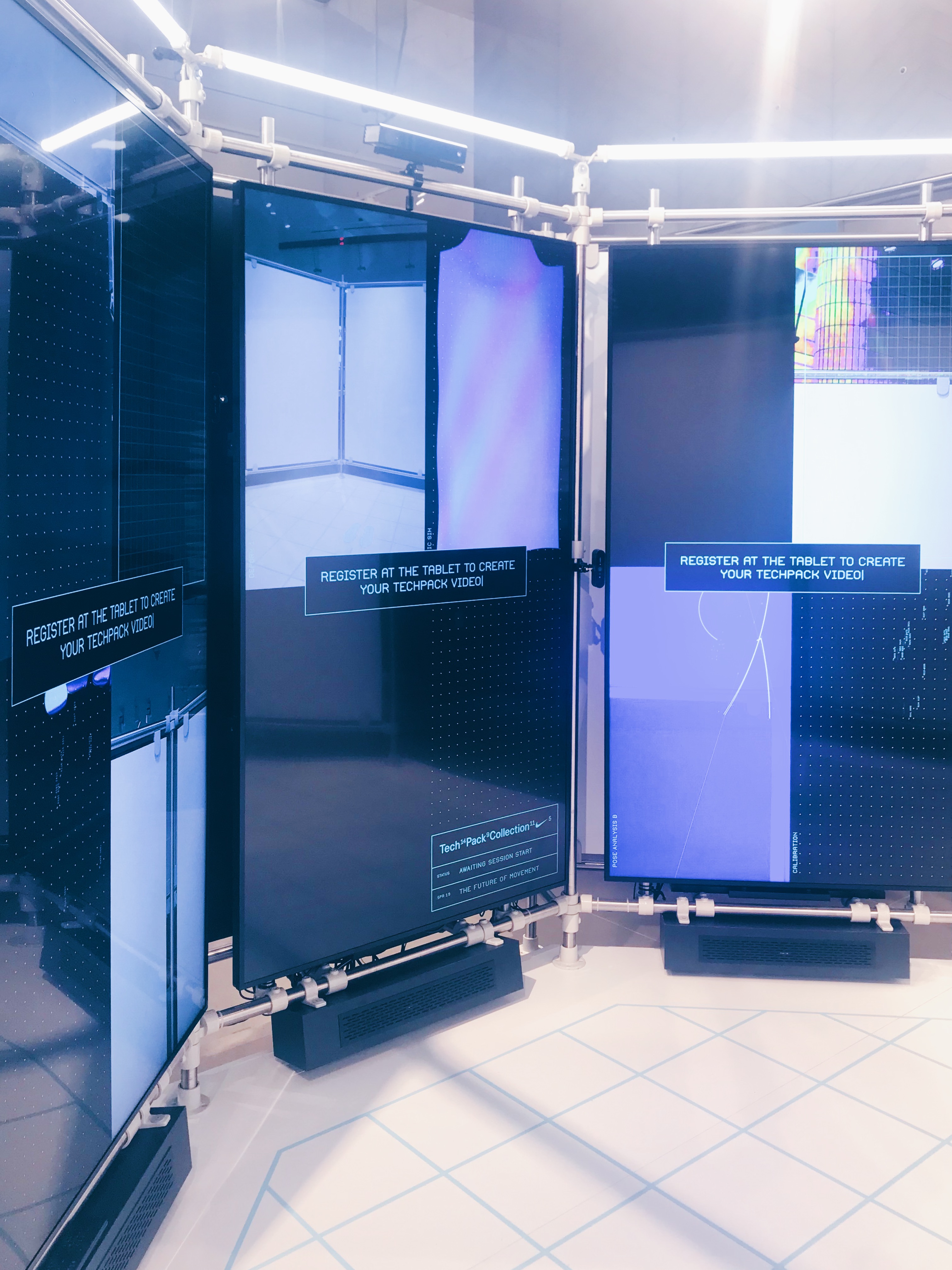

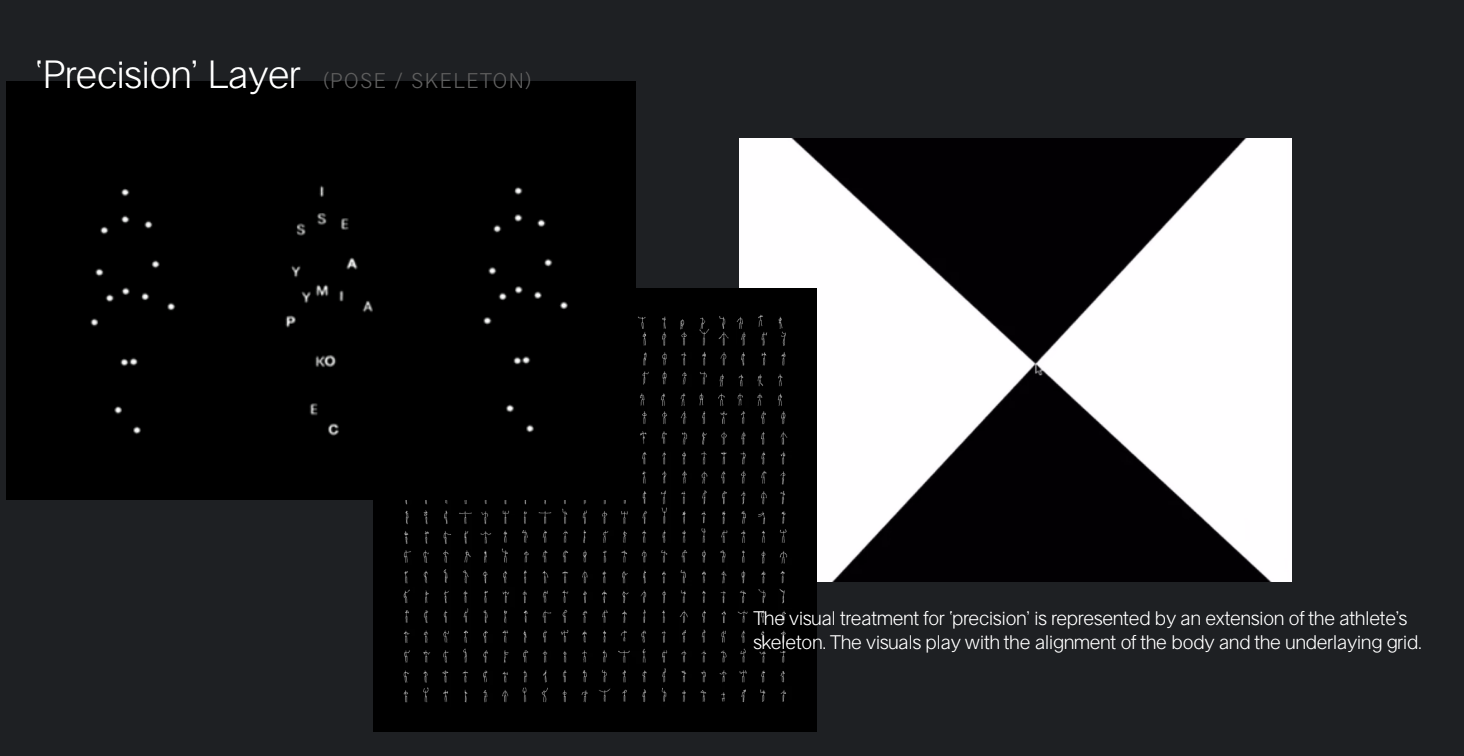

A big part of the User Experience design typically involves mirrors - whether physical (an actual glass mirror) or digital (a screen) - because a lot of people like looking at themselves, or need to see the "effect" being applied in real time. So this obviously favours programming animated graphics or live effects. For example, for a Nike "Tech Pack" campaign I helped to design and implement a range of on-screen graphics using C++ - typically either fragment shaders applied to live video frames or in some cases vector graphics representing "skeleton" (pose tracking) data from a Kinect:

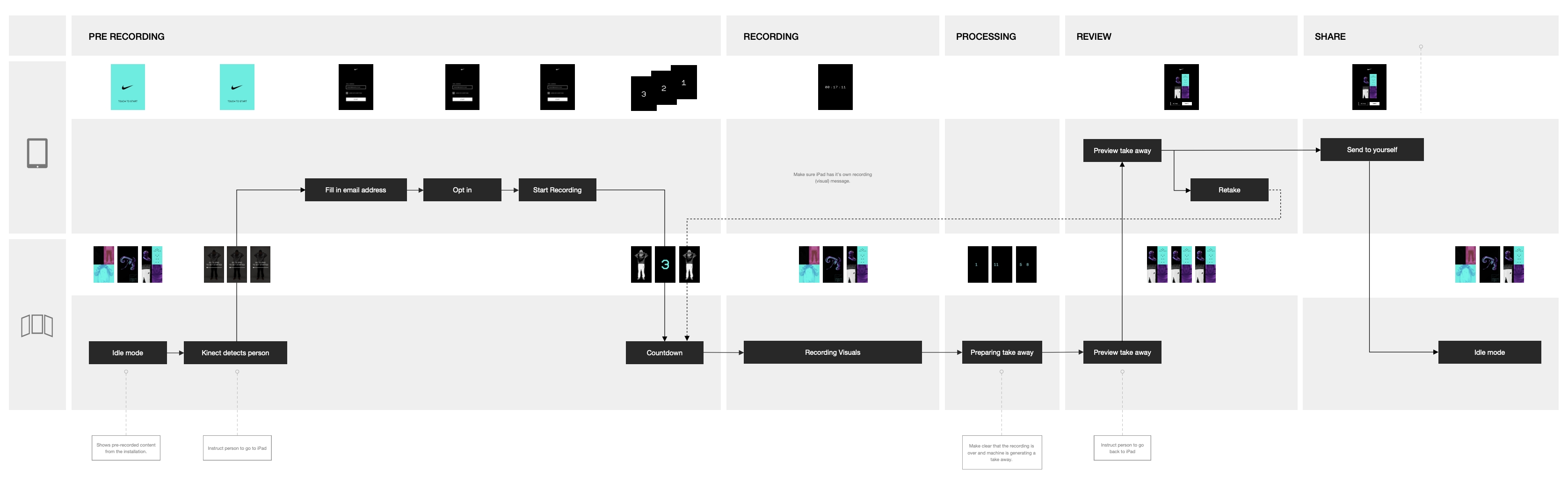

The entire user flow can often involve multiple stages with different hardware and cloud infrastructure requirements: mounted tablets, the user's own phone, multiple capture/output computers, cloud services for encoding, storing and emailing media, etc.

Full stack development

This is where I put a lot of "full stack development" into practice, as these sorts of projects required managing mobile applications, synchronising user sessions across multiple systems, handling user data securely and uploading/sending media via the Internet. NodeJS in general, and ExpressJS in particular, were used for the backend server tasks, whether running on-site or in the cloud - or, frequently, both.

Camera hardware

Then there are the video cameras themselves. Sometimes a webcam is good enough, but often you need much more of something: more software control, better lensing options, higher resolution, higher frame rate, etc.

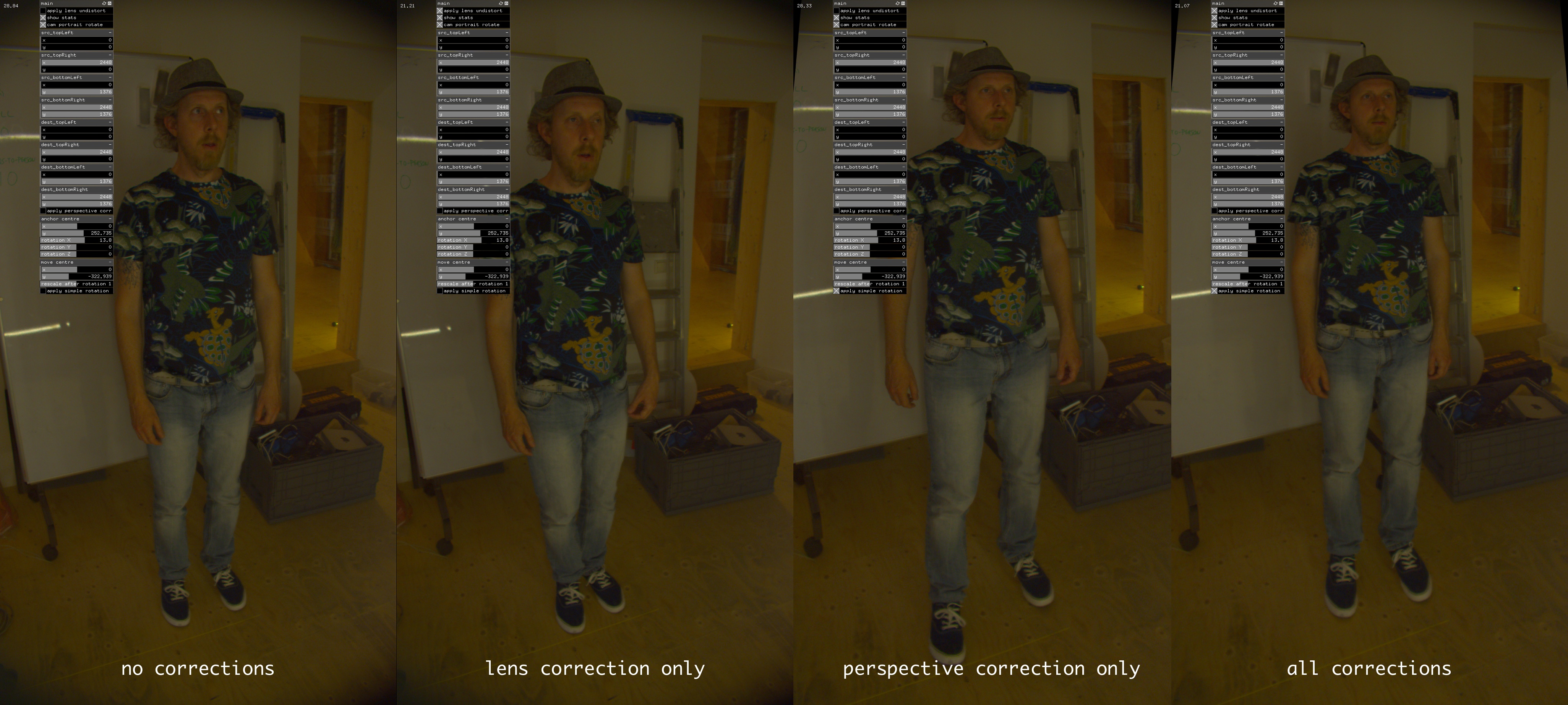

To get an almost "life size" image on screen from a very close position, for example, I used a Basler industrial imaging camera with a large sensor and high resolution, so that I could "undistort" the raw frames as close to realtime as I could manage, in this Selfie Mirror project for Tommy Hilfiger:

Industrial cameras are incredibly powerful when you need full control and the highest possible quality, but it does mean interacting with the manufacturer's own specialised SDK (usually in C+++) and doing a large amount of image processing yourself in order to achieve the results you're looking for.

Video processing

Next you have to do something with all the video frames you've captured and/or generated. Uncompressed image frames (even at "only" full-HD resolution) are surprisingly large - we are so used to compressed image formats such as JPEG that it's easy to forget that the raw information coming off a camera sensor can fill Gigabytes of memory within a few seconds! So buffering (in VRAM, or RAM) often becomes a thing you have to deal with as a developer. Hardware-encoding of video also helps enormously, although you have to be careful to only compress video frames after you've done the processing that requires the uncompressed pixels. Mastering streaming is what it's all about - whether that's USB-to-host, GPU-to-CPU, RAM-to-disk, process-to-process or over the network (e.g. using NDI).

"Editing" or switching between sources and/or titles or pre-generated graphics can either be done live or as part of a server-side process after capturing is completed. I became quite experienced building complex ffmpeg filter graphs in order to combine streams, apply filters (including audio processing) and encoding for upload.

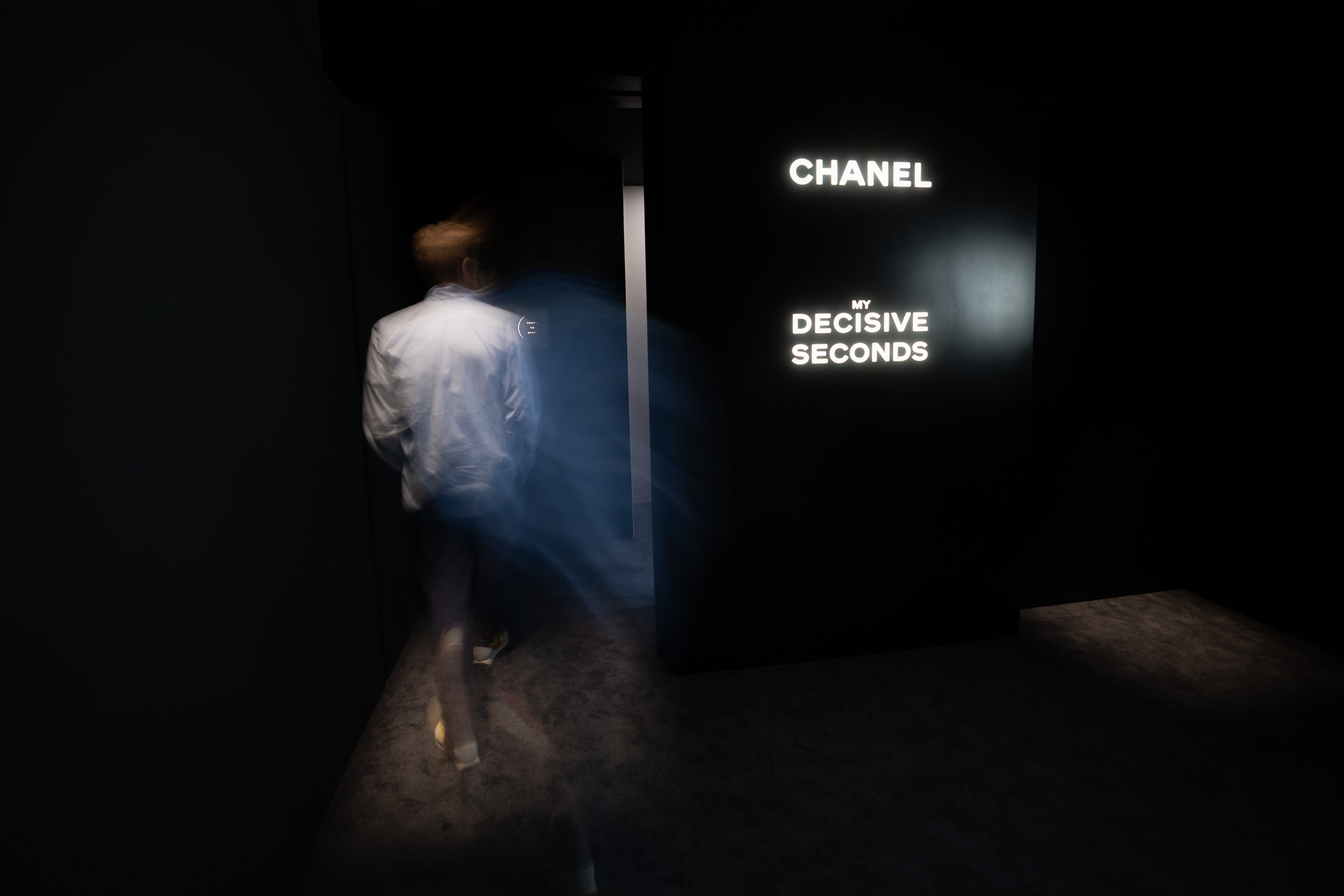

Capturing and editing live audio is one of the most challenging scenarios for a video-booth. This booth for Chanel looked beautiful and minimalist but required enormous care to conceal a microphone, time the recordings perfectly and automatically adjust and mix the final video within seconds of completing the experience:

Delivering (and managing) the final product

Finally you need to get the media to the user's device or social media account. I applied my experience with HTML emails, and MailChimp's Mandrill API, to good use here.

Finally, I really learned the value of good performance monitoring and metrics for these projects. Keeping an eye on all this infrastructure, often from thousands of kilometres away, was essential from the moment we were ready to leave the venue or retail outlet. But even while developing, it was incredibly useful to have data and centralised logging in order to track down subtle bugs in such a multi-layered system. Initially, I made some home-built libraries and tooling, but later found that a service such as Datadog covered our use case comprehensively.